How often do we find work that we love?

Few people end up doing what they love for their entire career. Sometimes, through a combination of interest, determination and circumstance, these happy few achieve mastery in their craft. At Zaic Design, we love meeting these people. We believe that the pursuit of mastery in one’s work can be an important source of meaning and satisfaction in life. Maybe it is even a key to human happiness.

In this series, we will try to understand how these unique individuals end up on their life course.

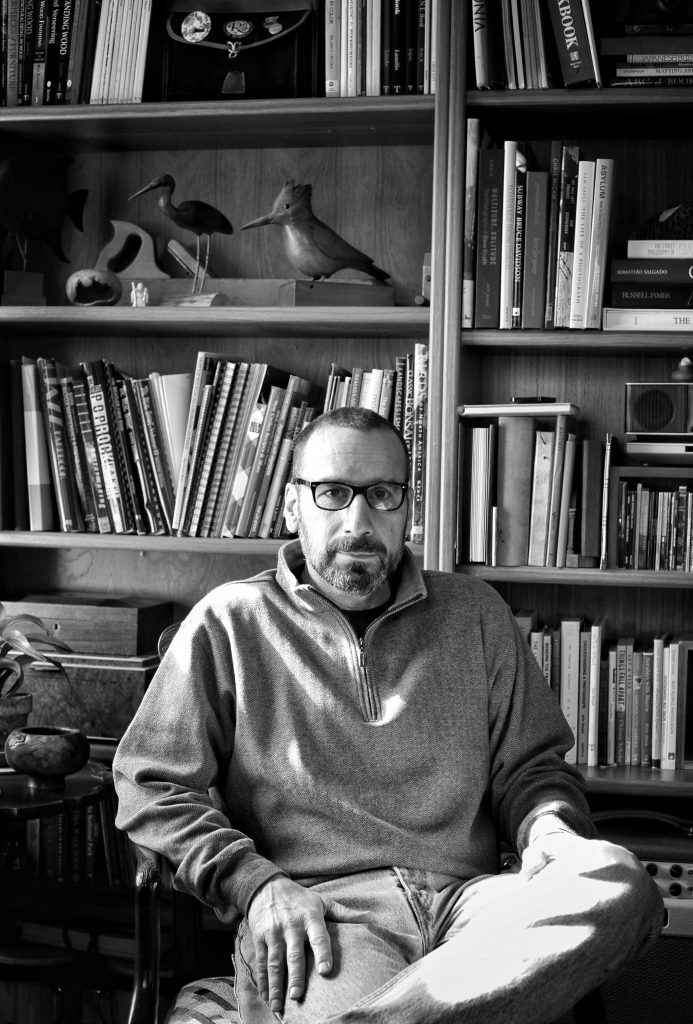

We sat with Paul Saporito in the living room of his apartment in northern New Jersey.

Paul poured us Japanese green tea as we flipped through albums of his black and white photos taken on the streets of New York City.

Paul has a magnetic board on the wall where he hangs his favorite new shots. As the months go by, he takes them down, one by one, until only the very best is left. That is the only one he keeps. You can see some of his street photos here.

This vetting process, this determined, unsentimental pursuit of perfection, is representative of Paul’s entire way of life. He owns very few things, but they are all perfect. At 57 years old, he rides a bicycle 14 miles to work, 14 miles home, except in extreme weather. The bicycle is built to his exact dimensions, and outfitted with boutique components of the finest quality, which each radiate a charm of their own. Finely stitched leather, gleaming polished aluminum, hand hammered steel.

We glance around the room and notice that every item of furniture is hand made. Sofa and chairs made by Paul. A miniature chest of drawers made by his father, in the tradition of 18th century cabinet makers, who carried miniatures as a physical portfolio of their artistry.

Paul learned cabinetry in his father’s shop. His great uncle was an immigrant from Italy who began working for Thomas Edison in his Victrola department before setting up his own shop. Paul’s father quit high school to work with his uncle and eventually set up his own shop as well, after fighting in World War 2 and coming home.

I asked Paul, “Did your father have any employees?”

“No, cabinetry was just something he was good at, so he could make a living at it. But it allowed him to do other stuff. You know, it was always camping, motorcycling, hunting, or something else.

I mean, I loved hanging out with my father. That was always where I was until he threw me out of the shop. I mean, you can’t have a 5 year old running around the shop, you have to get something done.”

Woodworking goes back a long way in Paul’s family. He knows that his father’s great uncle was a successful cabinetmaker in Italy. At that time, families in Italy had a trade that was passed down and kept in the family. For Paul, there is no one to pass the trade to.

I asked Paul how he developed his skill. Paul’s father was a quiet man. Whole days would pass with the two of them absorbed in their work, only a word or two exchanged between them. Sometimes his father would say something like:

“How many chairs have you seen me glue together?”

“Hundreds”

“Ever seen me glue one together like that?”

Paul’s father and uncle learned their craft in an environment where trade secrets were guarded. They were not accustomed to training others. You had to learn by watching, sometimes by sneaking glances at the right moment.

I asked Paul how he feels about the modern movement on the internet to share your workmanship secrets on Youtube. He said he sees the “proliferation of information as a good thing, because it means the craft can carry forward.”

“If someone asked me how I did something, I would never say no. I would be flattered that they would even be interested!”

To Paul, fine woodworking is not a dying trade because of lack of interest. It is dying because of lack of demand. Few people see value in paying for carefully crafted custom furniture when they can get something for far less money on the same day, at a local store or on the internet.

Paul ran his own furniture making business for 15 years after his father retired.

At a point, he realized that sales were flattening out, and that he was killing himself to make a decent living.

Just at that moment, he met Frank Pollaro, a master craftsman who had made a name for himself by producing some of the finest custom furniture in the world. Frank invited Paul to join his team. Paul saw this as a way to continue doing what he loved, and jumped at the chance to work with the other like minded, highly experienced craftsman that Frank had assembled.

This is where Paul continues to hone his craft, mentor the next generation of woodworkers, and produce breathtaking examples of the finest furniture that can be built.

Paul is someone I admire very much for his dedication to his work and his uncompromising pursuit of perfection. He brings to mind the archetypal Japanese sword maker, singly focused on the task at hand, but never becoming complacent about his skill. He constantly desires more knowledge, more access to other experts in specific areas of his field.

That seems to be the secret of his, or anyone’s, success at making their craft a life long love, not just a job. The drive for continuous improvement, and the humility to accept that there is always room to grow, even for a Master.

Photo Credit: Chris Zaic

0 Comments